The ugly duckling of Orange County: An architectural rescue

When I began my term as County Historian, Ted Sly was kind enough to go over some of his most memorable moments in the post. On one occasion around 2010, he explained, he met with members of the Paul Rudolph Foundation and toured them through the Government Center where they encountered hecklers, one of which shouted out from the office, “Tear it down! Tear it down!” It wasn’t my first inkling of the animosity that has persisted in the community regarding the Orange County Government Center since it was dedicated in 1970 but I appreciated his warning.

In 2012, just a year after super storm Irene flooded the building causing the County to move all government offices to temporary locations, historian Cornelia Bush scoured the minutes of the Orange County Board of Supervisors to build a timeline of Paul Rudolph’s relationship with the project. In her notes, she expanded on the discontentment expressed by local taxpayers due to cost overages and five years of legal battles with the construction company. The research in itself was necessary to dispel the misunderstandings that have been propagated over time by those who have advocated for or against the demolition of the building for almost 50 years.

I thank past County Historians Ted Sly and Cornelia Bush for compiling a body of research that I’ve been able to expand upon.

The 1962 regular session in which the task of interviewing architects was assigned to the “Buildings Committee” of the Orange County Board of Supervisors.

Paul Rudolph’s name first appears in Orange County records in 1963, a time when he had already established himself as a modernist home builder in Sarasota, Fla. and was serving as chair of the Yale Architecture School. The year before, he had completed the Temple St. Parking Garage, the first of two projects that, according to his 1997 obituary, would help “crystallize Mr. Rudolph’s reputation in the 60s.” The second of those projects, the Art and Architecture Building at Yale, would be completed by the time of his Jan. 1966 appearance in front of the Orange County Board of Supervisors. A trip to New Haven by any of the Board of Supervisors would have demonstrated Rudolph’s design capabilities and we can assume that they knew his design would be in a similar Brutalist style.

It is often asked why members of county government — seated in a traditional village like Goshen — chose to hire Paul Rudolph to design their new government center. And from what I’ve heard from the few officials who are still around today, it’s because they bought into the 1960s idea of bringing modern efficiency to government through state-of-the-art design. The purpose of County Government was expanding at the time and the Board of Supervisors needed to consider bringing on a manager to centralize operations. As the first County Executive, Lou Mills, who took office in January of 1970, explained it during a 2006 interview, “there was a trend at the time for the State to push human service problems onto the Counties, but they didn’t want to pass along funds” to provide for the added responsibilities. The Board of Supervisors brought in consultants and they recommended a new charter to create a County Executive and Legislature form of government.

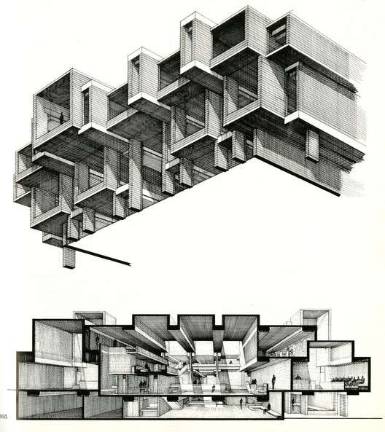

In the spirit of what Lou Mills calls a “tremendous change in the way the County operated,” the Board of Supervisors also decided to move from the 1887 building on Main St. to a new location. In 1963 the Board of Supervisors contracted the two “associated” architects Paul Rudolph and Peter Barbone to create a design and provide cost estimates. The Board of Supervisors secured funds amounting to $4,410,000 through a bond resolution in March of 1964, revised the estimated funds to $4,600,000 through bond resolution in April of 1965, and voted unanimously (with one absent) in May of 1965 to proceed with the firm. On Jan. 14, 1966, a special session was held for the architects to present their design to the Board of Supervisors. At the next regular session Feb. 11, 1966, a discussion ensued in which John McMickle from Middletown asked questions about the cost of the building and Henry Parry, Jr. from Highlands “addressed the chair and asked if the design could be ‘toned down’ a little, but stated he was in favor of the proposed building.” At vote, the resolution to approve preliminary sketches and authorize architects to “prepare working plans and drawings” passed with Ayes 31, Noes 4, Absent 1.

It’s not known how much of the structure was designed by Paul Rudolph, how much of the detailing was provided by Peter Barbone, and most significantly, how much was improvised by the two construction firms who interpreted the plans. By 1970 additional bonds were needed to cover the cost of construction which had ballooned to $6,489,000 — and by the time the building opened, the cost was $6,899,506.73. As per the initial contract, Barbone and Rudolph received 7.5 percent of construction costs as their fee.

Concerns about structural problems with the building and outrage over the cost increases cast a shadow over the opening ceremonies in December of 1970. Although when interviewed, Lou Mills stated that the building had “bad roofs and bad concrete” but added that to his recollection, “people enjoyed working there.” Whatever the sentiments, what’s clear is that the general construction firms Corbeau Construction Corp and Newman Construction Corp entered arbitration with Orange County which lasted for five years. During the time of arbitration, the County was not allowed to make repairs to the roof, exacerbating the leaks that had already started before opening day. During those legal proceedings, the construction companies claimed that Rudolph’s blueprints were incomplete, requiring them to spend extra time and capital in designing solutions. The arbitration was eventually decided in favor of the construction companies.

Over the decades that followed, the need to maximize the use of the square footage, requirements for handicap access, and contracting for regular repairs through an RFP bid process took its toll on the architectural vision of the Government Center. In my first memory of the building as a child, the sweeping steps in the courtyard were cracked and blocked off by yellow caution tape and the second floor offices were uncomfortably drafty.

It wasn’t until I saw the pictures so artfully taken by Joseph Molitor in 1970 that I realized this was once an architectural masterpiece.

But only a decade and a half had passed between that shabby appearance of my 1980s childhood and those beautiful photos. Members of the citizens coalition “Taxpayers of Orange County” that formed in 2011 to advocate for a full restoration of the structure allege that this deterioration of the building was avoidable, and furthermore that County officials were so embittered by the ballooned construction price and wasted legal funds that they rejected stewardship of the architectural signature elements.

The building was evacuated in 2011 after flooding and mold made the building hazardous for employees.

Paul Rudolph’s body of work became the subject of controversy almost immediately after construction. His Art and Architecture building at Yale was set on fire by student protestor in 1969 because, according to his obituary, they regarded “the building’s severe concrete design as a symbol of the university’s antipathy towards creative life.” Similarly, the Orange County Government Center was criticized for creating a cold and stark institutional space that distanced the elected officials from the public. By 1970, the year that the Orange County Government Center opened, Rudolph’s work was falling out of favor in the United States.

Gradually from the time of construction to the evacuation of the building in 2011, as the years took their toll on the structure’s functionality, the attitude that the building should be demolished took hold among the County Legislators via public sentiment. Meanwhile in art culture there was a revitalization of interest in Paul Rudolph’s work that began around the time of his death in 1997 and the building was featured on the World Monument Fund’s “Most Endangered” for 2012. The renewed interest from the public came just in time for this particular building, with pressure from community groups and international cultural organizations, the most iconic part of Rudolph’s design for Orange County was rescued and restored as part of the new construction plans. How this happened will be a topic for a future article.

If you are interested in the recent renovation of this Paul Rudolph masterpiece, visit Grit Works located at 115 Broadway in Newburgh to view an exhibition of photos by Isaac Diggs. The show “Home Sweet Home: Paul Rudolph’s Orange County Government Center” opened Nov. 25 and remains on display through Jan. 7.