What to Know About Monkeypox

An unfamiliar virus spreading fast. Sound familiar?

Here we are, well into year three of the COVID-19 pandemic, and now we’re having an outbreak of monkeypox? Is this a new virus? How worried should we be? While new information will continue to come in, here are answers to several common questions.

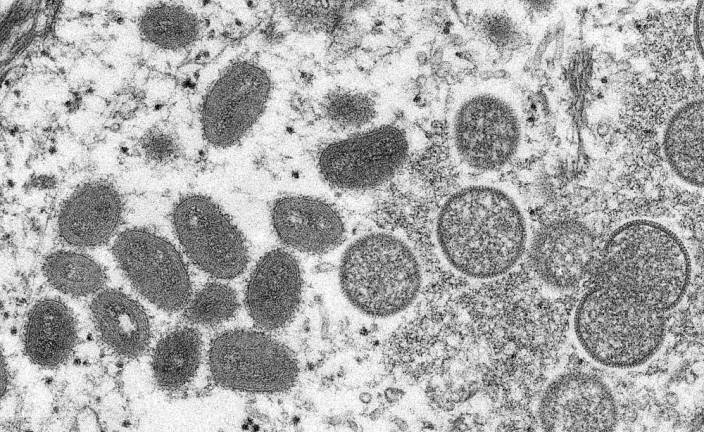

What is monkeypox?

Monkeypox is an infection caused by a virus in the same family as smallpox. It causes a similar (though usually less severe) illness and is most common in central and western Africa. It was first discovered in research monkeys more than half a century ago. Certain squirrels and rats found in Africa are among other animals that harbor this virus.

Currently, an outbreak is spreading fast outside of Africa. The virus has been reported in at least a dozen countries, including the U.S., Canada, and Israel and in Europe. As of this writing, Reuters reports more than 100 confirmed or suspected cases, making this the largest known outbreak outside of Africa. So far, no deaths have been reported.

Naturally, news about an unfamiliar virus spreading quickly internationally reminds us of the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. But monkeypox is not new—it was first discovered in 1958—and several features make it likely to be far less dangerous.

What are the symptoms of monkeypox?

The early symptoms of monkeypox are flulike, and include fever, fatigue, headache, and enlarged lymph nodes.

The rash that appears a few days later is unique. It often starts on the face and then appears on the palms, arms, legs, and other parts of the body. Some recent cases began with a rash on the genitals. Over a week or two, the rash changes from small, flat spots to tiny blisters (vesicles) similar to chicken pox, and then to larger, pus-filled blisters. These can take several weeks to scab over. Once that happens, the person is no longer contagious.

Although the disease is usually mild, complications can include pneumonia, vision loss due to eye infection, and sepsis, a life-threatening infection.

How does a person get monkeypox?

Typically, this illness occurs in people who have had contact with infected animals. It may follow a bite or scratch, or after consuming undercooked animal meat.

The respiratory route involves large droplets that don’t linger in the air or travel far. As a result, person-to-person spread typically requires prolonged, intimate contact.

Is monkeypox a sexually transmitted illness?

Monkeypox is not considered a sexually transmitted illness because it can be spread through any physical contact, not just through sexual contact. Some of the recent cases have occurred among men who have sex with men. That pattern hasn’t been reported before.

Can monkeypox be treated?

Yes. Although there are no specific, FDA-approved treatments for monkeypox, several antiviral medicines may be effective.

Can monkeypox be prevented?

Vaccination can help prevent this illness.

Smallpox vaccination, which was routine in the U.S. until the 1970s, may be up to 85 percent effective against monkeypox. The U.S. government has stockpiled doses of smallpox vaccine that could be used in the event of a widespread outbreak.

Additionally, the FDA approved a vaccine (called JYNNEOS) in 2019 for people over 18 who are at high risk for smallpox or monkeypox. The makers of this vaccine are ramping up production as this outbreak unfolds.

If you are caring for someone who has monkeypox, taking these steps may help protect you from the virus: wear a mask and gloves, regularly wash your hands, and practice physical distancing when possible. Ideally, a caregiver should be previously vaccinated against smallpox.

How sick are most people who get monkeypox?

Monkeypox is usually a mild illness that gets better on its own over a number of weeks.

Researchers have found that the West African strain of monkeypox is responsible for the current outbreak. That’s good news, because the death rate from this strain is much lower than the Congo Basin strain (about 1 percent to 3 percent versus 10 percent). More severe illness may occur in children, pregnant people, or people with immune suppression.

What else is unusual about this outbreak?

Many of those who are sick have not traveled to or from places where this virus is usually found, and have had no known contact with infected animals. In addition, there seems to be more person-to-person spread than in past outbreaks.

Is there any good news about monkeypox?

Yes. Monkeypox usually is contagious after symptoms begin, which can help limit its spread. One reason COVID-19 spread so rapidly was that people could spread it before they knew they had it.

Outbreaks occur sporadically, and tend to be relatively small because the virus does not spread easily between people. The last U.S. outbreak was in 2003; according to the CDC, nearly 50 people in the Midwest became ill after contact with pet prairie dogs that had been boarded near animals imported from Ghana.

Perhaps the best news is this: unlike SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, monkeypox is unlikely to cause a pandemic. It doesn’t spread as easily, and by the time a person is contagious they usually know they’re sick.

How worried should we be?

The growing numbers of cases in multiple countries suggest community spread is underway. More cases will probably be detected in the coming days and weeks.

It’s still early in the outbreak and there are many unanswered questions, including:

Has the monkeypox virus mutated to allow easier spread? Early research is reassuring.

Who is most at risk?

Will illness be more severe than in past outbreaks?

Will existing antiviral drugs and vaccines be effective against this virus?

What measures can we take to contain this outbreak?

So, monkeypox is no joke, and researchers are hard at work to answer these questions. Stay tuned as we learn more. Let your doctor know if you have an unexplained rash or other symptoms of monkeypox, especially if you have traveled to places where cases are now being reported.