Finding Benjamin Aske

By Sue Gardner

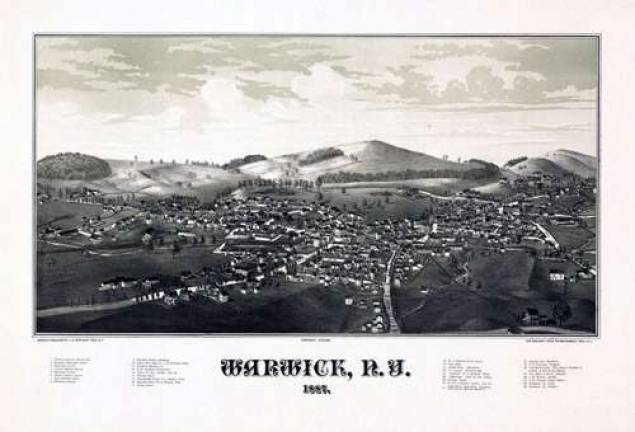

WARWICK — February is a month in which we celebrate the great political leaders George Washington and Abraham Lincoln, but what about Warwick's own founding fathers?

The man who named our own community, Benjamin Aske, is one of the least known figures in our history.

The facts known about his life were scarce: He was one of the 12 grantees of the Wawayanda Patent in 1702; his farm was south of the Village of Warwick on what is known as the Welling (Pioneer) farm; he was a wealthy merchant. He was friends with Thomas DeKay and is buried in the DeKay cemetery just over the border in New Jersey.

And he called his farm "Warwick."

If the stories are true, why do we know so little about him? A rich man surely would have left some sort of colonial administrative records.

1695: A New York Freeman

Our search began with the discovery that a man of the same name is listed in numerous transactions in "An Account of Her Majesty's Revenue in the Province of New York."

Beginning in 1701 we find he is an importer-exporter, bringing in casks and bales of goods such as clothing, wine and sundries. His exports are mainly furs, which England just couldn't get enough of.

But when did he come here, if he is already well set up by 1701? The earliest mention found is in a court case in 1694, and he is admitted as a New York Freeman - a status necessary for transacting business - in 1695.

From there, his career took off as the climbed the Colonial social ladder. He gained favor with the administration of Gov. Benjamin Fletcher and received valuable appointments. When the administration changed and Lord Bellomont came into power, however, he encountered choppy waters. The politics of the day were polarized and he was perceived to be on the wrong side.

In 1699 we find a letter stating that he is about to take ship to leave the colony. He is fed up with being harassed and hamstrung in his business dealings. He didn't leave, though, and enough oil was poured on the political waters that he weathered the changes.

The Cornbury Scandal

In 1702 the tide turned again in Aske's favor. Edward Hyde, Lord Cornbury-a cousin of Queen Anne-became Governor. Aske saw his chance to regain preferment and once again is receiving land grants such as Wawayanda, political appointments and large orders for his merchandise.

In 1704, he is so confident of his finances that in that the summer of 1704, he imports more than 1,000 gallons of brandy alone.

Benjamin is also more prone to getting into trouble; his close association with Cornbury has maddened his enemies, given rise to nuisance lawsuits. And he's had to borrow money.

The governor himself is in deep trouble, having acted in a profligate manner that has angered half the colony as well as made deadly political enemies in other provinces.

The story of Cornbury is interesting and the question of his "cross-dressing" and other character faults is detailed in the study "The Lord Cornbury Scandal" by Patricia Bonomi. He makes a strong case that although a difficult and mercurial man, Cornbury was the victim of a character assassination plot.

Cornbury is recalled to England in disgrace in 1708. Aske and his associates scramble to regroup and curry favor with the following administrations with little success. Benjamin has backed the wrong political horse.

Dire straits

Evidence of his dire straits was discovered in three letters in the Bodleian Library's Clarendon Collection by a "Benjamin Ashe." Written in 1711 to Cornbury in England, they begin with the easy familiarity of remembered good times and proposals for lucrative business schemes, but rapidly become desperate pleas for assistance:

April 27, 1711: "Capt. Symes & my Self sitting together in my Chamber drinking your LordShips Helth in a Tankard of Samson, Fell into discourse about the men of war & how the Queen might save a great Deal of money."

May 31, 1711: "...all the Costes of Courte will fall on me & I will begin a new action and before that can come to an issue the debt, which if I own I shall be almost undone, & therefore I most humbly beg that your Lordship would pleas to consider my Condition."

July 6, 1711: "I most humbly & Hartily beg that your Lordship will pleas to Stand my friend (for I have no other on whom I can depend) in procureing for Capt. Symes & my Self the post we have wrote for, which is now my only dependence."

All three letters appear to have gone unanswered. Comparison of the signature on these letters and that on a deed in the collection of the Warwick Historical Society prove that this is indeed "our" Benjamin Aske sending appeals to his one-time benefactor.

A few months later in 1712, we find that he has decamped from the city for his "wilderness property" in Warwick, one of the very first documented non-native arrivals. David Davis, in a legal deposition, states that he was living here with Aske in that year, on his farm named "Warwick." Although a political exile, he made the best of what he had left, made friends with other early settlers and spent the remainder of his days here.

He appears to have never married and died about 1737, as his estate is being offered for sale in 1738.

The question remains

Why did he name this place Warwick?

It has long been assumed that he was from Warwickshire, England.

However, professional genealogists find no trace of him there and the surname is one from further north.

Cornbury's wife, Catherine, died while in New York and was much beloved - one of her titles was a Baroness of Warwick. Perhaps Benjamin named his property in her honor.

Another possibility is that one of the Native American names for the area, Woerawin, sounds very similar; the Lenape Village of Mistucky was still active in the fields near base of the mountain, part of Aske's property.

We may never know exactly why we are "Warwick" but we do know that the continuing tradition of our community facing great challenges and finding a way to succeed in spite of them started very, very early.

Editor's note: Sue Gardner is the Town of Warwick Deputy Historian. For more information about Benjamin Aske, a copy of an expanded study is on display in the Albert Wisner Library's local history room or can be emailed by contacting sgardner@rcls.org.